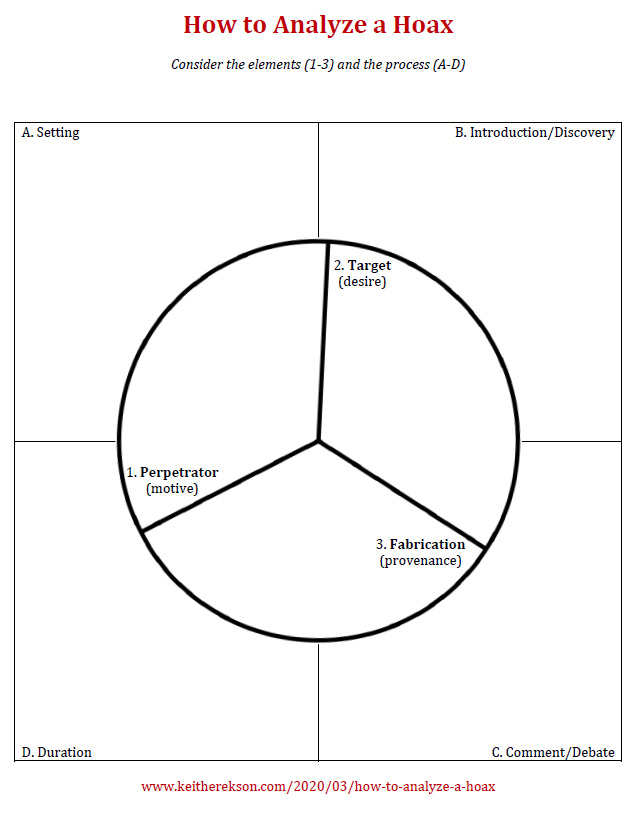

Hoaxes come in all shapes and sizes, but they employ the same basic elements—a perpetrator (with a motive), a target constituency (with an unmet desire), and a fabrication (with a provenance). Hoaxes also follow a common lifecycle—they play off their setting, are introduced or “discovered,” grow through comment and debate, and then endure or fade away.

The Elements

1. The Perpetrator. Perpetrators of hoaxes frequently possess charisma, attention to detail, and commitment to their cause. They may be motivated by fame, money, or power. They may want to show off, draw attention, push an agenda, exact revenge, or just “mess around.” Some may be sociopaths who are both anti-social and without conscience. My students added another motive to the list—to become savvy citizens in the 21st century.

2. The Target Constituency. Victims of hoaxes often possess reasons for not disbelieving—they are proud, indifferent, ignorant, or superstitious. If you think you can’t be conned, then you’re just the person a con artist wants to meet! Deep down, sometimes not even fully known to themselves, targets also possess an unmet desire that encourages them to believe—vanity, pride, or validation; personal prejudices or chauvinism; longing for financial gain, entertainment, or vicarious thrills. Even the inventor of Sherlock Holmes, the author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, was tricked by photographs of fairies.

3. A Fabrication. Every hoax must fabricate something—an artifact or item, an entity or person, facts or information. We call the fabrication a forgery if the perpetrator manufactured the entire new work. We call it a fake if an authentic object is altered, with the addition of a forged signature or something like that. But neither a forgery or a fake can simply spring out of nowhere, so the most important part of a fabrication is its provenance, or the story of where it came from and how it arrived on the scene today.

Con artist-turned-reality-TV-star R. Paul Wilson asserts that the formula for tricking any person is simple. X + Y = Z. People will believe any lie (Y) so long as it relates to a fact (X) and leads to a deep desire (Z). For example, it is true that eating healthy matters (X), so I can sell you an unproven “dietary supplement” (Y) if you desire easy results guaranteed (Z)!

The Process

A. Setting. Hoaxes play of their time and place. They are more common:

- in times of stress and upheaval (less common in times of stability),

- when there are clear divisions between us/them (less common with unity),

- when migration is restricted (less common with easier flow),

- when cultural authority wanes (less common when church and state align),

- during periods of scientific and technological change (less common when consensus).

B. Introduction/Discovery. After a perpetrator has manufactured a fabrication and courted a target constituency, the hoax begins when a “discovery” of the fabrication. In time its invented provenance comes out.

C. Comment and Debate. The “best” hoaxes are not too perfect or complete but have wiggle room to grow in public comment and debate. The debate galvanizes supporters and detractors as people take sides. Additional “supporting” evidence can be added to the conversation. Participants become invested as they contribute to the dialogue. Often an “unsuspecting champion” emerges who is also a target/victim of the perpetrator and has good credentials within the target community.

D. Duration/Longevity. Some hoaxes garner brief attention and then disappear quickly. Others endure to become persistent parts of the community or culture.

Putting the Pieces Together

Here’s a look at how the elements and process came together with the Elvis Presley Book of Mormon forgery.

1. Perpetrator (with a motive)

Unknown

2. Target Constituency (with an unmet desire)

Latter-day Saints who desired

- A story of individual change and redemption (Elvis from sinner to saint)

- A story of collective redemption and legitimacy (validation from a celebrity)

- An “inspiring” story to tell (to “promote faith”)

3. Fabrication (with provenance)

A copy of the Book of Mormon with forged annotations purportedly made by Elvis Presley (that surfaced through an Elvis fan who joined the Church in 1976)

A. Setting

- Late 1980s

- Elvis Presley and his parents have died (no one to contradict the story)

- Not a lot of Elvis memorabilia on the market yet (hard to verify)

B. Introduction/Discovery

- Attempt 1: Fan tries to sell book to a dealer who declines

- Attempt 2: Fan tells Osmond family that Elvis wanted them to have the book

C. Comment and Debate

- Osmond family becomes first victim/unsuspecting champion

- Book donated to the Church in 1989

- Accepted with little scrutiny by archivists or journalists

D. Duration

- Widely reported by speakers, writers, journalists for 30 years

- Inspired a movie in 2007

- Analysis of context and handwriting reveals forgery in 2018

You Try It

- One of the new corona virus hoaxes

- A recent hoax from 2018

- Something from the Museum of Hoaxes

Published by the History News Network on March 15, 2020.

Two hoaxes surfaced on the Internet in late November and early December 2019. The hoaxes drew interest and comment, prompted clicks and reposts, and fooled both the unsuspecting and the highly trained. The hoaxes did not spark widespread panic or promise essential health cures; they were not created by marketing bots or Russian spies. The hoaxes were designed, planned, and launched by my undergraduate students at the University of Utah as part of their preparation to become savvy citizens in the twenty-first century.

One hoax announced the “discovery” of a wedding ring in Frisco, Utah, bearing the inscription “Etta Place – Chubut, 1904.” A photograph of the ring was enough to excite Facebook users to fill in the gaps. “Etta Place was the girlfriend of Henry Longbaugh aka the Sundance Kid,” wrote one. “Chubut is the province in Argentina where the couple settled,” added another. “I thought I knew pretty much all of the legends of Butch and his companions,” observed a third, “I’m looking forward to the rest of the story.” This ruse met its match in a museum professional who pointed out that the dirt in the photo did not reflect the composition of soil from southern Utah and that a gold ring would not have fractured like the tungsten ring in the photo.

The second hoax “uncovered” a document in the university archive with implications for a collegiate rivalry. A first-year graduate student “found” an architectural sketch indicating that the statue of Brigham Young on his namesake campus in Provo was originally intended to fill a pedestal that remains empty to this day on the campus of the University of Utah. Then an ardent “fan” created an online petition calling for the return of a statue with a Twitter hashtag to #BringBrighamBack! BYU fans seemed amused, while a Utah fan retorted “Please keep the name and the statue!” One reader knowingly stated that he’d “already heard” this as an urban myth and was glad the answer was finally found in the archives. A professor from one of the schools read the petition, clicked through to the faked study, and then reposted the underlying study.

Why teach students to create hoaxes? First and foremost, we need citizens with the skills and perspective to survive in “the golden age of hoaxes.” Photoshopped images and deep faked videos go viral on social media, cable channels air documentaries about mermaids and monsters, celebrities become politicians, and politicians call the media “fake.” And yet, what circulates so quickly on the Internet today also circulated in other forms in the past—forged diaries and documents, a mermaid body washed up on shore, photographs of fairies or Lincoln’s ghost, and tales of life on the moon.

Teaching about hoaxes also represents good professional practice. I taught the course as a night class at a university, but by day I am the director of an archive/research library where I am responsible both to share information and preserve its integrity for perpetuity. My library joins the Smithsonian among the countless victims of the most notorious murderer-forger in history. We follow the best practices of the archival profession for providing secure access in our reading room. Our IT professionals constantly monitor for phishing, social engineering, or outright hacking. One way to protect the historical record is to understand how it can be stolen, manipulated, modified, or erased.

Teaching with hoaxes also presented an opportunity for engaging pedagogy. In designing the course, I took cues from psychologists who examine abnormal mental dysfunction to promote better mental health, from police officers who experience tasers and K-9 takedowns before being authorized to use them, and from athletes who run the plays of opponents in order to beat them. If we are to avoid being fooled by bad information, we must understand how it works. How better to understand how it works than by creating our own hoaxes? We began by exploring the history and methods of past hoaxers, frauds, and forgers. We sought usable lessons by developing skills in the historical method to identify and debunk false claims and by seeking to understand how digital misinformation and disinformation circulate today.

The students succeeded in creating hoaxes that fooled some in their target audiences, but our creations faced stiff competition on the worldwide web of misinformation. Both hoaxes ran for about two weeks before we came clean. Those weeks also witnessed presidential impeachment hearings by the House Judiciary Committee, a rumor about the height of Disney’s most famous animated snowman, and a Facebook hoax about women being abducted in white vans. One of the takeaways noted by my students was that it was hard to get people’s attention in an environment in which they are constantly bombarded by misinformation.

The experience also prompted increased respect for actual professional expertise. The group working on the fake ring explicitly targeted baby boomers, thinking they’d be an easy target. That intergenerational spite dissipated after their best effort was so effortlessly debunked by someone with more experience.

Other lessons learned came out of the ongoing classroom discussions about the ethics of our activities. After all, it’s not every day that one gets assigned to forge a historical document, photoshop an image, create fake social media accounts, and spread deception on the Internet. We drew a line that prohibited the forgery of medical claims, soliciting money, public harm, or anything that would get any of us arrested, fired, or expelled. That left us free to experiment with information, history, and emotional appeal.

The discipline of history has much to offer our present age of misinformation in terms of subject matter and analytical methods. Here’s hoping for a future in which we recognize the flood of misinformation around us, acknowledge the value of expertise, and develop the thinking skills necessary to survive our century.

Keith A. Erekson is an author, teacher, and public historian who taught a night class on “Hoaxes and History” at the University of Utah in the fall 2019 semester. Learn more at keitherekson.com.

Each day, from March 15-21, I’ll share information and resources from the class I taught last fall at the University of Utah on “Hoaxes and History.”

Look forward to information such as . . .

- Why I taught my students to create hoaxes

- How to analyze a hoax

- How to detect a hoax

- Top 10 free online tools for detecting hoaxes

- Reading recommendations on past hoaxes

Join in the conversation on Twitter or Facebook.

Don’t Be Fooled!

The Church History Library houses the sacred and valuable historical records of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. If your family has been associated with the Church in the United States or in other countries, these records can help bring your family’s story to life.

Records and Collections

The Church History Library holds millions of original, authoritative historical records, including official church records, diaries, memoirs, personal papers, letters, photographs, oral histories, and local-unit Church records. The records are stored in climate-controlled vaults and are accessible to researchers in the reading room. Many records have been digitized and are also available online.

Free Online Resources

Church History Catalog

The Church History Catalog is the principal resource for searching the Library’s archive, manuscript, and print collections. Simple and advanced searches for names, places, and topics yield results that may be narrowed by material type, date, and language. Wildcard and Boolean searches are also supported. Millions of digitized images are added to the catalog each year and users may recommend sources for future digitization. Materials in the catalog come from a wide spectrum of sources and represent numerous points of view. Users of the catalog should not assume that the Church or the Library endorses every item in the collection.

Database of Early Missionaries

The Missionary Database documents every known Latter-day Saint missionary from 1830 to eighty years ago. The database currently lists more than 42,000 individuals with links to images of thousands of original and authoritative records. The database can be searched by name or browsed to find sources and photos. (Use your FamilySearch login to identify your ancestors in the database.)

Database of Overland Pioneers

The Pioneer Database attempts to document every Latter-day Saint overland pioneer who traveled to Utah between 1847 and 1868; it is the product of more than two decades of work. The database currently lists more than 57,000 individuals with links to thousands of original and authoritative records of pioneer experience. The database can be searched by name or browsed to find sources and photos. (Use your FamilySearch login to identify your ancestors in the database.)

Day-by-day Chronology of Church History Events

The Journal History of the Church is a chronological, day-by-day compilation of Church history events from 1830 to 2008. Taken mostly from newspapers but also from correspondence, diaries, letters, sermons, minutes, and accounts, this 1,200-volume collection contains valuable historical and biographical information. Indexes may be searched for names of individuals, places, church units, and events. Digital images of the index cards and the corresponding pages of the Journal History of the Church are available in the Church History Catalog.

Index of People Named in the Joseph Smith Papers

The Joseph Smith Papers Project is an effort to gather all extant Joseph Smith documents and to publish them with both textual and contextual annotation, including brief biographical sketches for selected persons mentioned therein. Names listed in this index include church leaders and members, Smith family members, people Joseph Smith encountered in his travels, parties involved in legal and business matters, and other acquaintances. (Use your FamilySearch login to identify your ancestors in the database.)

Index of Letters Written to Brigham Young

The Brigham Young Office Files contain approximately 15,000 letters from Church members who sought personal guidance, spiritual advice, or financial help from Brigham Young between 1844 and 1877. Many letters report on missionary matters and colonization progress. The index letter of writers together with digital images of the letters can be accessed through the Church History Catalog. Researchers may also consult letterpress copybooks for replies to letters.

Index to Periodical Articles by and about the Church

The Church Periodical Index enriches access to articles related to the Church and its history by indexing all significant articles in Church-produced, English language magazines, namely, the Ensign, Liahona, New Era, Friend, and Church News. The index also points to content in selected other periodicals, regardless of perspective, that contribute to the study of the history, doctrine, and culture of the Church. The index contains more than 165,000 entries and is searchable through the Church History Catalog.

Answers to Your Church History Research Questions

Click on the “Ask Us” button anywhere you find it in the catalog or on our web pages to submit a question to our archivists, librarians, historians, conservators, curators, or records managers.

Visit the Church History Library

Visit the Library in person Monday through Saturday at 15 East North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84150-1600. Visit the Library online today at ChurchHistoryLibrary.org.

Bonus Links

- Find people named in early Relief Society records. (Use your FamilySearch login to identify your ancestors in the database.)

- Request a copy of an ancestor’s patriarchal blessing.

- Consult research guides for topics including sources on family and local history, the Perpetual Emigrating Fund (PEF), blacks in church history, women’s organizations, women’s suffrage, and much more.

As part of the bicentennial celebration in 2020, the Church History Library has placed original records of the First Vision on display in its ongoing “Foundations of Faith” exhibit.

Published in the Church News, February 1, 2020.

One’s understanding of history is always enriched when one considers the insights from multiple accounts of past events. During his lifetime, Joseph Smith repeatedly testified that God the Father and Jesus Christ appeared to him, taught him about individual redemption and instructed him about the kingdom of God on the earth.

The earliest surviving account of the First Vision was written by Joseph Smith in the summer of 1832 as part of his personal history. After spending time pondering and reflecting on the great mercy of God, he penned a deeply personal account that described both his consciousness of his own sins and his frustration at being unable to find a church that matched the one he had read about in the New Testament that could lead him to redemption. He explained that from the age of 12 he worried about “the welfare of (his) immortal soul” and thus spent years searching the scriptures before offering his prayer. When Deity appeared to him, he asked how to be forgiven of his sins, and this account emphasizes Jesus Christ’s Atonement and the personal redemption it offers. Joseph wrote that he felt love and joy for many days after the experience.

Joseph Smith’s journal contains another account of his vision, written by one of his scribes in the fall of 1835. When a visitor arrived in Kirtland asking about the Church, Joseph recounted his experiences in seeking to know which church was right. This account mentions the opposition he felt as he prayed and the appearance of one divine personage who introduced another. This account uniquely notes the appearance of angels during the vision.

The exhibit also presents accounts of the vision that were published during Joseph’s lifetime. The earliest published account was prepared by Orson Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for a pamphlet published in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1840. Joseph later drew on this pamphlet in responding to Illinois newspaper editor John Wentworth to describe the rise of the Church and the important Articles of Faith.

A second pamphlet, published by Orson Hyde in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1842, also drew from Pratt’s account. Hyde was returning from dedicating the Holy Land for the gathering of the remnants of Abraham’s scattered posterity and published the account in German as part of the early effort to sound the gospel message to the entire world.

A first edition copy of the Pearl of Great Price contains Joseph’s most widely known account of his First Vision. Joseph began work on a longer history in 1838 that was compiled by scribes under his direction and completed after his death. Writing in context of troubles in Kirtland, violence in Missouri, and confinement in Liberty Jail, this later history positions the First Vision as the beginning of “the rise and progress of the Church.” The portion of the history describing the vision was published in the Times and Seasons newspaper in Nauvoo in 1842.

Nine years later, the excerpt was re-published in England as part of a pamphlet containing some of Joseph’s writings, translations and revelations that was compiled by Elder Franklin D. Richards of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and titled “Pearl of Great Price.” The pamphlet was canonized by unanimous vote at the October 1880 general conference.

High-resolution images of the documents are available online. The Church History Library is open Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., with extended hours on Thursday evening until 8 p.m. and on Saturday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Arrangements may also be made on the library’s website for group visits that include special downtown parking and a historical presentation. Admission to the library is free and the public is welcome.

I’m happy to report that Mormon Women’s History–with its two award-winning chapters–will be released in paperback in March 2020.

The book is already available cloth and e-book versions.

Visit the book’s page on my website to learn more, download a chapter, or purchase copy.

Tags

Access Policy Analogies Angel Moroni Archives & libraries Awards Black history Careers in History Church History Library Church History Speaking Come Follow Me Commemoration Conspiracy Theories Contingent Citizens Databases Elvis Presley Forgery Everybody's History Family History & Genealogy First Vision Foundations of Faith Genealogy Speaking History Skills History teaching & learning Hoaxes and History 2019 How History Works In the Church News Kirtland Temple Lincoln Making Sense of Your Patriarchal Blessing Missionaries Mormon studies Mormon Women's History Mother's Day Patriarchal Blessings Pioneers Politics Primary sources Questions and Answers RealvsRumor Saints Saints (narrative history) Sensible History Stories Texas social studies UTEP Centennial WitnessesDisclaimer

The views expressed here are the opinions of Keith A. Erekson and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Church History Department or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.