The October 2020 issue of the Journal of Mormon History features a forum on archival access, with an article I wrote about access in the Church History Library.

My article traces the history of access in the Church’s collection, explains all of the factors that go into making access designations, and describes recent changes that make our current era the best time for researching the history of the church:

Older researchers sometimes speak wistfully of a bygone era of research in the 1970s, but perhaps those fading memories of “Camelot” can be replaced with the current benefits of “pajamalot.” Our present era allows unprecedented access for researchers working from the convenience of their own homes at any hour of the day.

Erekson, “A New Era of Research Access,” p. 129.

Full article citation: Keith A. Erekson, “A New Era of Research Access in the Church History Library,” Journal of Mormon History 46, no. 4 (2020): 117–29, https://doi.org/10.5406/jmormhist.46.4.0117.

Episode Summary: Keith Erekson is the director of the Library Division of the Church History Department. In this episode Keith explains a conflict between members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Keith also describes how the First Presidency was reorganized after the disunity was resolved.

Listen to Episode 37: To the Throne of Grace.

Today, Cornell University Press releases an exciting new book featuring fourteen essays that track changes in the ways Americans have perceived the Latter-day Saints since the 1830s. From presidential politics, to political violence, to the definition of marriage, to the meaning of sexual equality—the editors and contributors place Latter-day Saints within larger American histories of territorial expansion, religious mission, Constitutional interpretation, and state formation. These essays also show that the political support of the Latter-day Saints has proven valuable to other political groups at critical junctures.

The volume includes chapters by Keith A. Erekson, Adam Jortner, Spencer W. McBride, Benjamin E. Park, Natalie K. Rose, Amy S. Greenberg, Thomas Richards Jr., Brent M. Rogers, Stephen E. Smith, Matthew C. Godfrey, Matt Mason, Rachel St. John, J. B. Haws, and Patrick Q. Mason. It was was edited by Spencer W. McBride, Brent M. Rogers, and Keith A. Erekson.

Visit the book’s page on my website to learn more, download a chapter, or purchase copy.

Episode Summary: Keith Erekson is the director of the Library Division of the Church History Department. In this week’s episode we explore the cooperative movement of the Church. We also learn about a visit by Joseph Smith III to Utah Territory.

Listen to Episode 24: An Immense Labor.

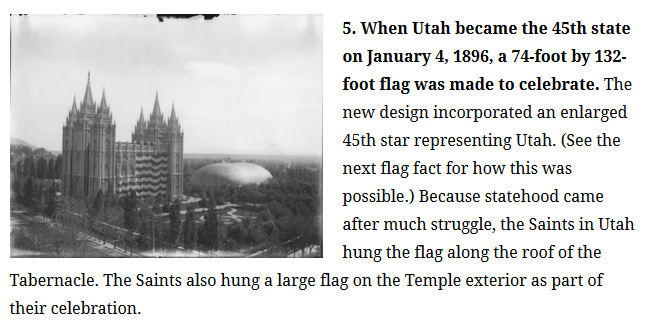

The cover of Contingent Citizens features a photograph of the Salt Lake Temple draped in an enormous American flag. We thought this juxtaposition—church and state, piety and patriotism, sacred and secular—captured the complex and contradictory ways that Latter-day Saints have been perceived in American politics. In the book we tease out the tensions clustered around authority and mobilization, power and sovereignty, and unity and nationalism. But the image prompts other interesting questions about the flag itself and how it ended up on the side of the Church’s most well-known Temple.

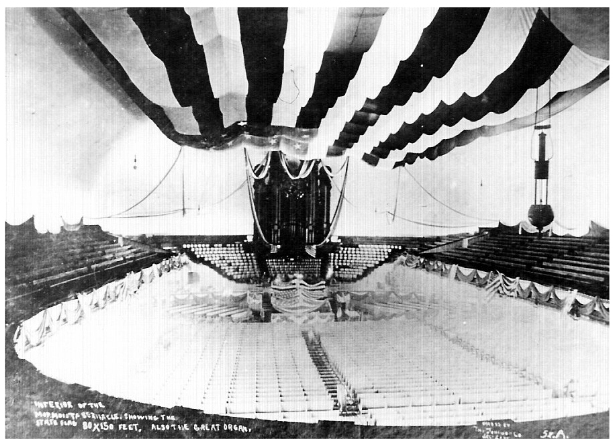

Why such a large flag?

The flag was created to celebrate Utah’s admission as a state in 1896. With dimensions of 132 feet by 74 feet, it was designed to be “the largest flag in history” and it held that title until 1923. U.S. President Grover Cleveland signed the proclamation admitting Utah on January 4 and on January 6 an inauguration ceremony was held in the Tabernacle on Temple Square. The flag covered most of the ceiling and at the specified moment in the program a switch was flipped to illuminate Utah’s new 45th star on the flag.

Why was it hung that way?

The flag remained in the Tabernacle for several months, but as plans developed to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the pioneers in 1897, the large flag needed to find a new home. Over the next six years, until around 1903, it hung on the south side of the temple for appropriate holidays.

No records survive to document why the flag was hung in this way, but contextual information provides some clues. The flag would have fit on the north or south sides of the Temple, and they chose the south. The flag had two sides (the side with the blue union on the left hung in the Tabernacle), so they chose the side with the union on the right. Placement on the south side of the Temple made the flag visible to the more numerous city streets to the south. The Temple’s tallest towers on the east (with the angel Moroni at center) serve symbolically as the flagpole, with the colors thus flying in the breeze as it moves forward to the east. It was not until 1942 that the U.S. Congress adopted the United States Flag Code, with its prescriptions for flag hanging. Thus, there were no official instructions in 1897, but a circular from the U.S. War Department’s adjutant general issued in 1917 recommended that flags hung flat on walls should be oriented with the union to the north or east.

It is okay that the past was different?

Of course. As we seek to make sense of the pieces of the past and the stories told about it, we discover people, places, experiences, and traditions different from our own. The hanging of the flag “backwards” was not intended as a sign of disrespect or defiance. It did not preemptively break a flag code that would be passed half a century later. It was an appropriate part of its own time and place.

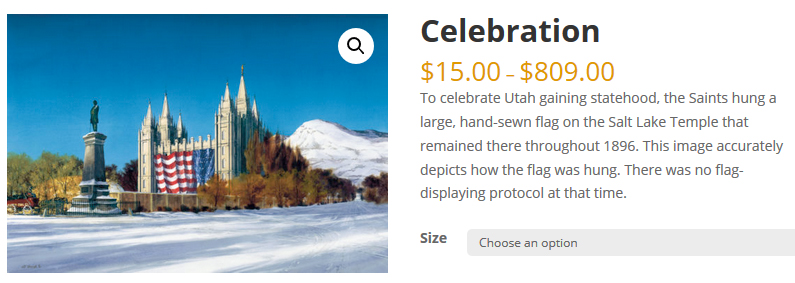

One artist who painted the scene as a romanticized pastoral landscape, felt no qualms about removing of all of the buildings and other signs of urban life, but nevertheless felt the need to explain: “This image accurately depicts how the flag was hung. There was no flag-displaying protocol at that time.”

Perhaps suspecting that its modern readers would be embarrassed, a magazine catering to the lives of Latter-day Saints inverted the image, a move made obvious by the presence of foothills in downtown Salt Lake City on the left edge of the photo.

Sources

The image on the cover of Contingent Citizens comes from the George W. Reed Photograph Collection the at the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library’s Special Collections.

For more on the history of this and other large flags, see John M. Hartvigsen, “Utah’s Mammoth Statehood Flag,” Raven: A Journal of Vexillology 19 (2012): 27–56. (Vexillology is the study of flags, their designs, histories, and uses.)

How do you detect and avoid a hoax? It’s difficult, and the better the hoax the tougher it is to detect. There is not a single “answer” or “trick” or “secret.”

A magician writing in a Cold-War era manual for international spies explained that “practically every popularly held opinion on how to deceive, as well as how to safeguard one’s self from being deceived, is wrong in fact as well as premise.” The hand is not quicker than the eye and “there is never a single secret for any trick.” Rather, “a trick does not fool the eye but fools the brain.” Thus, the antidote involves careful observation, thinking, and analysis. We must become aware of human limitations and perpetrator methods and we must employ thoughtful counter-strategies and helpful tools.

Awareness of Your Own Human Limitations

Perpetrators exploit the weaknesses of human thinking and observation. First, there are social limitations. We seem to have an innate sense of trust; we assume that what we experience is true. The existence of society is predicated on our trust that parents are kind, leaders are just, and neighbors are friendly. Because it is not humanly possible or feasible to verify everything, our minds create shortcuts for evaluating the world around us—we trust if it comes with experts and endorsements, if it contains scientific formulas or graphs or photos of scientists, if we feel pleasant emotions.

We also possess mental limitations. We are more likely to remember things that have a memorable story or pattern. Our minds tend to imbue patterns with intention and meaning, and we can end up seeing patterns or messages in randomness (pareidolia). Our minds prefer information that is easier to process—whether because of high contrast, rhyming, or simplicity. We remember things that align with what we already believe (confirmation bias) and ignore information that runs counter to our existing beliefs (motivated reasoning). Increased familiarity with things gives us the illusion of validity (illusory truth effect). Once we form inaccurate beliefs, they become heard to eradicate, even after clear correction (continuing influence effect). Sometimes, we cannot see our own incompetence (Dunning-Kruger Effect).

Awareness of Perpetrator Methods

Researchers have identified several common principles employed by perpetrators in a variety of schemes. They can distract you into focusing on something that grabs your interest so that you miss everything else (common in magic tricks). They count on social compliance, or the way that most people are trained by society not to question authority (employed in social engineering or phishing). The herd principle describes the way that most people follow everyone around them (used in auctions with a planted bidder or in social media aliases). The dishonesty principle expects that each person has a little larceny on the inside (people may be willing to rationalize the purchase stolen goods if they are a “good deal”). The kindness principle accepts that most people are fundamentally nice and willing to help (exploited in scam requests for disaster aid). Con artists exploit need and greed, because our deeper drives, moods, and pain shape what we really want (often paired with distraction). Finally, the time principle recognizes that people make worse choices under pressure (when presented with a “limited time offer”).

These general principles work with a variety of tactics. Perpetrators of hoaxes and scams might present fake experts and anonymous sources (such as non-traditional news outlets and amateur publications), appeal to ancient wisdom or alternative options (secret knowledge), deny the conclusiveness of evidence (“we can’t be sure”), seek only for evidence that supports their position (cherry picking), emphasize only strange things (anomaly hunting), present a large quantity of information (proof by verbosity), set criteria that no one could meet (impossible expectations), or change the requirements (moving the goalposts).

Thoughtful Counterstrategies

To avoid being tricked by a hoax or scam you will need more than common sense. You will need more than the usual simple tricks. You cannot simply trust websites that end in .org (hoaxers use them because most people trust them).

Sam Wineburg and the Stanford History Education Group recommend a practice they call “lateral reading.” Instead of down a webpage to review its official-looking logo or domain name, you should learn to leave the page and look around it on the internet. Open up a new browser window and search for situational details—Who hosts the site? What can you find from other sources about the site owner? Who links to the site? (Here are curriculum materials for teaching these skills to students)

After you’ve determined something is a hoax, how do you persuade others who still believe? You must provide factual alternatives (not just vague statements). You must refute misinformation by explaining why the myth is false and why the facts are true (not just state that something is incorrect). Where possible, present information in a way that affirms a person’s worldview and is congruent with their values. And foster healthy skepticism.

Tools and Resources

Here are our top 10 free online tools for detecting hoaxes:

- Snopes.com fact checks urban legends, hoaxes, and folklore.

- Hoax-Slayer exposes email and social media hoaxes as well as current internet scams.

- The Internet has an official registry in which to search for a website’s owner and creator.

- Google’s reverse image search can be used to find where an image appears elsewhere on the web.

- Tin Eye searches the web for images and offers a “compare” feature that highlights any differences caused by cropping, resizing, skewing, or other manipulation.

- FotoForensics reveals if an image has been modified.

- Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer reveals information about the creation of specific digital images.

- Amnesty International has created the YouTube Data Viewer that reveals when a video was originally posted and extracts image thumbnails that can be reverse searched

- WolframAlpha offers a powerful knowledgebase for checking all kinds of information

- Wikimapia hosts maps with all kinds of interesting geographic information

After you’ve identified a hoax, use these tools to analyze it!

Tags

Access Policy Analogies Angel Moroni Archives & libraries Awards Black history Careers in History Church History Library Church History Speaking Come Follow Me Commemoration Conspiracy Theories Contingent Citizens Databases Elvis Presley Forgery Everybody's History Family History & Genealogy First Vision Foundations of Faith Genealogy Speaking History Skills History teaching & learning Hoaxes and History 2019 How History Works In the Church News Kirtland Temple Lincoln Making Sense of Your Patriarchal Blessing Missionaries Mormon studies Mormon Women's History Mother's Day Patriarchal Blessings Pioneers Politics Primary sources Questions and Answers RealvsRumor Saints Saints (narrative history) Sensible History Stories Texas social studies UTEP Centennial WitnessesDisclaimer

The views expressed here are the opinions of Keith A. Erekson and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Church History Department or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.