This text is re-posted from Rachel Sterzer, “Top 10 Treasures in the Church History Library,” Church News, September 9, 2016. The original contains many photographs, and some errors.

The Church History Library, located at Church headquarters in downtown Salt Lake City, is a special place, said the library’s director, Keith A. Erekson. The library houses a quarter of a million books and magazines as well as manuscripts, thousands of audiovisual materials, two million photographs, and many other artifacts that document the history of the Church in the latter days.

The Church goes to great lengths to preserve these treasures. The library retains secure storage vaults and is built to the highest seismic standards. It is climate controlled to reduce fluctuations in temperature for items that are temperature sensitive. It is also secured with cameras and sensors and lasers and “everything we need to keep the records safe,” Brother Erekson explained.

But amid the library’s trove of historical objects and documents are some extra special items. During a session of BYU Campus Education Week, Brother Erekson shared what he considers to be the “Top 10 Treasures of the Church History Library.”

10. President Hinckley’s sketch of small temples

In the 1880s the Church sent several families to northern Mexico to settle. They built a community—Colonia Juarez—including a school that continued to operate 100 years later. President Gordon B. Hinckley traveled there to celebrate the school’s centennial and on the four-hour drive back to El Paso, Texas, began thinking about the Saints he had met.

“[He thought] about their faith, about their history, about their long ties to the Church,” Brother Erekson said. He also thought about how the Saints had to travel six hours across international boundaries to go to the temple in Arizona.

On the plane ride from El Paso to Salt Lake City, President Hinckley sketched the plans for small temples, which he immediately presented to the Church architects, Brother Erekson said. By the October 1997 general conference, President Hinckley announced that they were going to experiment with small temples in Colonia Juarez, Mexico; Monticello, Utah; and Anchorage, Alaska. By July of 1998, the Monticello Temple was completed—13 months from idea to fruition, Brother Erekson noted.

In the April 1998 general conference, President Hinckley announced plans to construct 30 smaller temples immediately, in addition to 17 temples already under construction, to make a total of 47 new temples, plus the 51 then in operation. After naming the countries where the new temples were to be built, President Hinckley said, “I think we had better add two more to make it an even 100 by the end of this century, being 2,000 years ‘since the coming of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in the flesh’ (D&C 20:1). In this program we are moving on a scale the like of which we have never seen before” (“New Temples to Provide ‘Crowning Blessings of the Gospel,’” Ensign, May 1998).

“You remember how startling that was?” Brother Erekson asked. “The document of that revelation—of how he worked out the details and followed through—is preserved in the Church History Library.”

9. Emmeline B. Wells’s editorial in the Woman’s Exponent

In the late 19th century President Brigham Young called Emmeline B. Wells, who was serving in the General Relief Society Presidency, into his office. “He tells her, ‘We’ve been here in the valley for 30 years and I have been asking the men to save grain and they haven’t done anything, so I give up. So I’m asking you. I know you’ll get it done,’” Brother Erekson related.

As the editor of a women’s newspaper, the Woman’s Exponent, Sister Wells immediately penned an editorial issuing the challenge by the prophet. “And the sisters began that very day storing grain.”

In the early days, the women stored and used the grain to help those within their own community, but by the 20th century they began sending it to help others in need. They sent grain to help survivors of the San Francisco fire and to China following a devastating earthquake, Brother Erekson explained. During World War I, they sold the grain to the federal government, invested the money, and used the interest to provide insurance and medical assistance to pregnant women and their children.

“So we can see the roots of the Church’s welfare services, humanitarian services, and social services programs.” The impact of those women’s dedicated service goes back to Emmeline B. Wells and her editorial in the Woman’s Exponent, he said.

8. The letter from Liberty Jail

When Joseph Smith was incarcerated in Liberty Jail, he dictated a letter to his scribe, Alexander McRae, who was also there. Joseph signed it. His brother Hyrum signed it. All of the men jailed with the Prophet signed it. In 1876 parts of the letter were used as sections 121, 122, and 123 of the Doctrine and Covenants.

“But the actual letter that Joseph dictated, that a scribe wrote, that they all signed, is there in the Church History Library,” Brother Erekson shared.

7. Joseph Smith’s first journal

Two years after the Church was organized, Joseph Smith sat down for the first time in his life and started to record his activities.

“Joseph Smith was very aware that he didn’t have a lot of education,” Brother Erekson explained. The Prophet became a very good speaker but never became comfortable as a writer, which is what makes his journal “so precious,” Brother Erekson said. The journal captures his handwriting but also captures his inadequacy.

On the first page of the journal, the first sentence is scratched out. Joseph writes, “Oh may God grant that I may be directed in all my thoughts. Oh bless thy servant, Amen.”

“He can’t even get through the first page without a prayer for help because this is hard for him,” Brother Erekson said. “It’s a very precious record of his life and his experience.”

6. Wilford Woodruff’s copy of the Book of Commandments

In 1833, Mary Elizabeth Rollins and her sister, Caroline, saved a pile of printed revelations from an angry mob in Independence, Missouri, by gathering the pages, running, and hiding in a cornfield.

Shortly after, the salvaged pages were combined with other pages to create a tiny book called the Book of Commandments. “Individual members of the Church hand stitched their own personal copy of these revelations,” Brother Erekson explained. Only 29 copies of the book survived. The Church History Library owns six copies. The Library of Congress has one. Many are in private collections.

“This is one of the rarest and most prized items in all of American book publishing and collecting,” Brother Erekson said.

One of the copies in the library’s possession belonged to Wilford Woodruff. Brother Woodruff kept a few blank pages at the back of his copy. When Joseph Smith received the revelation known today as section 89 of the Doctrine and Covenants—the Word of Wisdom—Brother Woodruff handwrote the revelation in the back of his book.

Wilford Woodruff’s handwritten, signed copy of the Book of Commandments “is one of the great treasures of Church history and we’re happy it is in the library,” Brother Erekson said.

5. Fragments of the papyrus scrolls

Brother Erekson explained that the library has 11 fragments that date back to about 200 B.C. “Obviously these are not the things that Abraham wrote on. Papyrus does not last that long. These are copies of copies of copies of copies.” Brother Erekson said they are unsure where the fragments fit within the scrolls that Joseph translated as the book of Abraham.

The scrolls were uncovered in Egypt in the early 1800s and made their way through dealers and collectors to Italy, then to New York City, and then to Ohio, where Joseph purchased them. After translating the book of Abraham, Joseph gave the scrolls to his mother, Lucy Mack Smith.

Brother Erekson said historians’ best guess is that the scrolls were separated when the Saints left Nauvoo. There is historical evidence, he said, that a museum in Chicago was collecting the material before being consumed in the fire of 1871. The fragments now on display in the library were discovered in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1967 before being acquired by the Church.

“They’ve all been digitized and are online on the Joseph Smith Papers website. They’ve never been on display publicly until just a little bit ago.”

4. Hyrum’s copy of the Book of Mormon

“You may recognize this book,” Brother Erekson told attendees, noting that Elder Jeffrey R. Holland held it up in the 2009 October general conference.

The book belonged to Hyrum Smith’s wife and has a page folded down in the book of Ether where Hyrum was reading before he left for Carthage, where he was murdered with his brother the Prophet Joseph Smith.

“This book is one of the precious things connected with Hyrum Smith’s life and the end of his and Joseph’s [lives] and one of the great treasures that we have in the library,” Brother Erekson said.

3. 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon

Only 5,000 copies of the first edition of the Book of Mormon were printed in New York City in 1830, Brother Erekson explained. Today, somewhere from 500 to 700 survive.

“This is the kind of book that the first generation of converts read. The second edition wasn’t published until 1837. … If your family encountered the Church from 1830 to 1837, this is the Book of Mormon they would have somehow seen or read or borrowed or heard read aloud or found a way to learn about and pray about. This is the edition that Brigham Young read, that Eliza R. Snow and Lorenzo Snow read, that Heber C. Kimball read,” Brother Erekson said.

2. Original manuscript of the Book of Mormon

Brother Erekson explained that when Joseph Smith completed translating the gold plates, he gave his scribe, Oliver Cowdery, an assignment—make a copy of the whole manuscript.

“We call that copy the printer’s manuscript,” Brother Erekson said. “That’s the copy they took to the printer to do the typesetting, and Joseph kept the original manuscript.”

When the Saints settled in Nauvoo, Joseph put the original manuscript in the cornerstone of the Nauvoo House. “It stayed there for 40 years until the house is kind of crumbling. When they open up the cornerstone, water had gotten in and they find a soggy mess,” Brother Erekson said.

Today, historians have been able to recover about 28 percent of the original manuscript. Through the Joseph Smith Papers project, the printer’s manuscript has been digitized and is available online.

1. Patriarchal blessing records

“We have all kinds of treasures, but of all of the treasures we keep, I think … the most important for every member of the Church is that we keep the official record of your patriarchal blessing.”

Brother Erekson then gave listeners a special invitation to come and “see these treasures.”

“All except your patriarchal blessing are on display at the Church History Library. I personally invite you to come up and take a look at the originals. See them there. Bring your family. Bring your friends.”

The excitement and value of Church History will be my theme during four presentations at Brigham Young University’s Campus Education Week on August 16-19, 2016.

Church History Can Help You!

1:50–2:45 p.m. in 222 Martin Building (MARB)

T The Top 10 Treasures in the Church History Library

W Use Church History to Understand Your Patriarchal Blessing

Th Find Your Family in Church History

F Answer Questions about Church History

The Top 10 Treasures in the Church History Library

The Church History Library houses the Church’s official archival, manuscript, and print records and among its collections are found many wonderful treasures. This presentation will share stories and high-quality images of each treasure, employing a top-10-style countdown to reveal them. Attendees will be invited to see the treasures in person.

Use Church History to Understand Your Patriarchal Blessing

The Church History Library holds the official copies of patriarchal blessings submitted by patriarchs. It also holds thousands of journals, talks, and letters that document the efforts of Church members and leaders to follow the counsel in their individual blessings. Drawing from published comments, the presentation shares experiences in understanding and interpreting one’s own patriarchal blessing.

Find Your Family in Church History

The Church History Library holds millions of original, authoritative historical records such as diaries, memoirs, personal papers, letters, photographs, and oral histories. Learn how to use these records to uncover historical experiences, personal and family history, and priesthood lineage.

Answer Questions about Church History

This presentation reviews sound principles for making sense of history.

A few years ago, a copy of the Book of Mormon surfaced in the Church History Library that was thought to have been given to Jesse N. Smith by Joseph Smith. Speaking today the Jesse N. Smith Family Reunion, I explained why this is not the book and how to find and identify the actual book.

About the Presentation

- Summary of Main Ideas (published in the Church News, July 8, 2016)

- Selected Slides from the Presentation (PDF)

- Authentic Jesse N. Smith Items in the Church History Library (PDF)

Authentic Sources for Jesse N. Smith

- Portrait of Jesse N. Smith, c. 1864 (Church History Library)

- Autobiographical Sketch, c. 1884 (also published in Andrew Jenson’s LDS Biographical Encyclopedia, vol. 1 (1941), pp. 316-322.)

- Statement, 15 February 1894 (Church History Library)

- Journal, 1904-1906 (Church History Library)

- General Conference Address, April 1905, pp. 50-52

- See also Jesse N. Smith in the Early Mormon Missionaries Database

An important part of every Pioneer Day celebration involves rehearsing the stories of the pioneers. Stories about the past inspire us today, and they become more effective as they become more complete and accurate.

An important part of every Pioneer Day celebration involves rehearsing the stories of the pioneers. Stories about the past inspire us today, and they become more effective as they become more complete and accurate.

In the Church History Library, our historians, archivists and librarians have recently worked to learn and tell a better story about a book that has been in our collection for nearly 70 years. I share this behind-the-scenes view of the process in the hopes that it may help improve your family stories.

This Pioneer Day, may we seek to gather all of the pieces of the past that survive and to record all of the family stories that can be told. May we ask good questions that help us read the sources, stories and artifacts closely. May we have discernment to corroborate those facts which can be established and humility to hold on to the questions that remain unanswerable, at least for now.

1. Distinguish the past from stories and questions.

We must first distinguish the past from the stories told about it. The past is gone and the pioneers who lived through it have passed away. Some pioneers told stories about what they experienced and why it was important to them. Their stories are collected, retold (and sometimes embellished) by descendants for many reasons — to entertain, to instill gratitude, or to win an argument.

Today, we can tell better stories by asking good questions about the past and about the stories told by others. Our inquiry is shaped by the sources and stories available, but also by our own assumptions, values and needs. We will likely begin with more questions than answers, but that’s OK because each question gives us a place to start thinking.

In our case, the stories told about a book in our vault caused us to ask: Did Joseph Smith give a Book of Mormon to his cousin, Jesse N. Smith? What happened to the book? Is the book in our vault the one that was given to Jesse?

2. Read closely to corroborate details.

Good questions lead us to look for all of the pieces of the past and stories that we can find — stories written or remembered, books on library shelves, artifacts in attics or heirlooms in trunks. Once found, read closely and ask additional questions: What kind of source is it? Who was the author or creator? When and where and for whom was the source created or the story told? What is the main idea and what evidence supports it? What remains missing or untold?

In the case of Jesse N. Smith, we found an autobiographical sketch in which he stated that Joseph Smith gave him a copy of the Book of Mormon in 1843. We also discovered that Jesse told the story at general conference in 1905, repeating the fact that a Book of Mormon had been given while emphasizing that it was not a first edition (published in 1830) and that it bore a beautiful binding.

3. Read closely to identify provenance and verify authenticity.

We must likewise closely read material artifacts. Was an artifact actually created in the past? Did the purported user actually use it? Where has the artifact been since its creator or user last possessed it?

In the case of the book in the library’s vault, we found that it contained a handwritten inscription on the inside front cover, a typed note pasted in, and some handwriting beneath the note. The inscription stated that the book was given to Jesse N. Smith in 1842. But, as noted above, Jesse said he received the book in 1843. This error suggests that the inscription was not written at the time, a conclusion corroborated by the fact that the handwriting did not match known samples by Joseph or Jesse. The typed note stated that the book was donated to the Church in 1948 by the president of the Mesa Arizona Temple, so we could begin to establish the book’s provenance — the chain of custody from past to present. Other questions remained as yet unanswerable: When was the book donated to the temple? By whom and for what reason?

The handwriting beneath the note said the book had been repaired in 1944, but a closer look at the physical artifact revealed that the “repair” had been very invasive. The spine of the book had been removed entirely and replaced with a flexible substance called buckram. The first and last pages (including the title page) were missing, and those that remained had been roughly stitched together, leaving them uneven and too tight to open. The text matched the layout and typesetting of this edition printed in Liverpool, England, in 1849 — six years later than Jesse reported receiving a book and five years after Joseph had died.

Thus, by comparing Jesse N. Smith’s stories with the artifact in our vault, we concluded that yes, Joseph Smith did give his cousin Jesse a Book of Mormon, but no, this particular artifact is not that book. Most likely, a descendant who recalled Jesse’s story found this 1849 edition, added an inscription, had it repaired, and then gave it to the temple. This means that the actual book given by Joseph to Jesse may yet be out there somewhere, in a library or attic or trunk. When the actual book is discovered, there will be an even better story to tell.

This essay was published in the Deseret News on July 7, 2016.

This article was published in the Deseret News (online) and in the Church News (print). On my blog I summarized this talk and shared the story of Sarah Stageman’s conversion and pamphlet.

Mormon women’s history ‘at a crossroads,’ speaker says

By R. Scott Lloyd, LDS Church News

Published: Thursday, March 17, 2016

PROVO, UTAH

The director of what he terms “the largest single repository of Mormon women’s history sources in the world” declared that such history stands at a crossroads today.

The director of what he terms “the largest single repository of Mormon women’s history sources in the world” declared that such history stands at a crossroads today.

Keith Erekson, director of the Church History Library, was the opening plenary session speaker March 3 for the annual Church History Symposium sponsored by the Church History Department and the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University. The theme of this year’s conference was “Beyond Biography: Sources in Context for Mormon Women’s History.”

“Being at a crossroads in the 21st century isn’t all bad, considering that about a century ago in Mormon women’s history, we were at a no-roads,” Brother Erekson remarked.

“In the earliest [recorded] histories of the Church, women were typically absent,” he said. “In contrast to these Church histories, women were very present in anti-polygamy literature in the 19th century. They’re described as victims, … as defenseless, as slaves, de-literated, downtrodden, dull, senseless, sorrowful, degraded, shapeless, miserable.”

The next generation of writers in the Church responded to such portrayals defensively, he said, and “that defensive stance has really been a part of writing about Mormon women ever since.”

At the turn of the century, in B. H. Roberts’ six volume History of the Church, he presented Mormon women as “noble-minded, high-spirited, intelligent, courageous, independent, cheerful, profoundly religious, capable of great sacrifice,” Brother Erekson noted.

Thus, by the time the Church passed its first century mark, Mormon women had been portrayed variously “as absent, as victims, as profiled notables, as placeholders of designated spaces, and as symbols,” Brother Erekson said.

“It would be left for another generation of writers to ask, ‘Who were these women? Would we recognize them? Whose are the faces under the big-brimmed, pioneer sunbonnets?’ ”

Later in the 20th century, “Mormon women historians began to look at women and their experience with polygamy, their experience as men left on missions,” he said. “This generation found women active in the Relief Society and other auxiliaries, active in Utah politics and the national quest for suffrage. We began to explore and understand in ways we never had before the leading sisters of the earliest generations of the Church’s history.”

Brother Erekson said that at this point, a crossroads, it is appropriate to ask: “How can we place their lives and their stories in context? What can be learned from more systematic analysis?”

Much, it turns out, largely because of the proliferation of sources of late.

In the Church History Library alone are some 9,000 diaries and autobiographies of which nearly 1,600 are written by women, Brother Erekson said.

A team of cataloguers processes about 500 print and rare materials a month, he said. “I also have a team that processes our archival materials, collections that range from maybe two or three letters to 150 boxes of letters and correspondence and papers. We work through about 300 of these collections a month.”

He invited history enthusiasts to come to the library but said they don’t even have to do that to access its holdings. The library has worked in partnership with BYU to post digital images that can be accessed through history.lds.org.

“Today we have 6.8 million digital images available right now on the catalog; 2.7 million were digitized in 2015 alone,” he said.

Brother Erekson announced to the audience that the library has now published “a brand new research guide to women and Church history; you’re the first to hear about it.”

He said, “Go to our website. Click on ‘Women in Church history.’ … We’ve got links to the minutes, to the handbooks, to periodicals, to the histories. We’ve included research hints. … For example, the Young Women organization in the Church has had about half a dozen names over its history. So one of the hints here tells you what those names are and what years the names applied so you could find the kinds of records you would be looking for.”

Brother Erekson said another way the library is working to make sources available digitally is to provide sources cited in the new “Gospel Topics” essays at lds.org, which cover such topics as Mother in Heaven, and Joseph Smith’s teachings on priesthood and women.

Brother Erekson invited researchers to be creative in the way they use sources, to pay attention to the function women served in the Church as well as the form, and to work harder to uncover women’s participation in institutions.

“Look at impact; look at change,” he said. “That story is told from the perspective of conversion. … We might look at our Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel Database not as a record of people who walked but of people who converted. And we could start to find them and ask about their experience. Together with the new missionary database, we’ve got powerful tools to look at the story in a larger scale.”

Brother Erekson concluded his lecture with some “don’ts.”

“Don’t omit women. Ever.

“Don’t just add women somewhere as a vignette or a sidebar or a chapter or a section or on a pedestal.

“Don’t see women only as wives and daughters and as auxiliary members. There’s so much more to be seen, to be understood, to be contextualized.

“Don’t think that women’s history is only for women or for historians.

“Finally, don’t assume that you have seen all the sources.”

This story of Sarah Stageman–her conversion, her conviction, and her pamphlet–provides a compelling example of how each person can think clearly, value fairness, and quench bad information (pages 157-158).

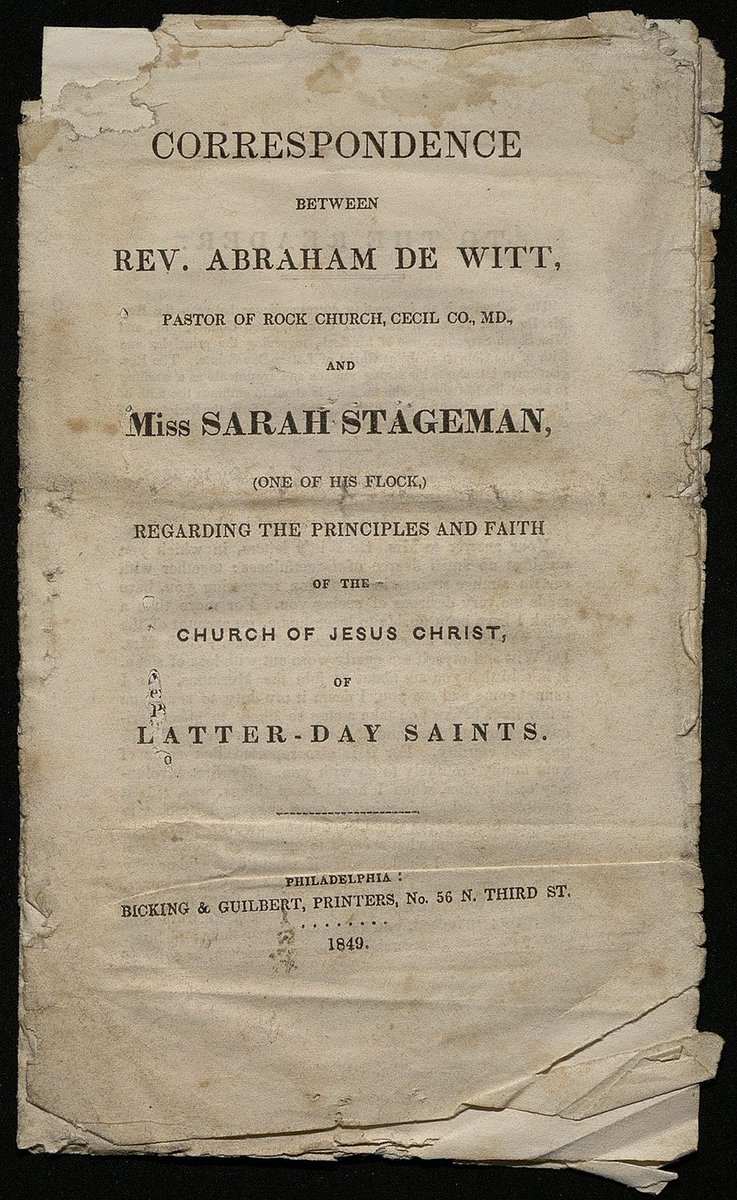

Recently, the acquisitions team in the Church History Library encountered a pamphlet that was not part of our collection. It was understood to be an anti-Mormon pamphlet from 1849, but as we studied its text and placed it into historical context, we discovered that the pamphlet had been gravely misunderstood.

The pamphlet opens with a caustic letter by Rev. Abraham De Witt, the Princeton-educated pastor of Rock Presbyterian Church in Cecil County, Maryland. He condescendingly chastises a young girl for even considering the Church, declaring that she has an “excitable and unstable mind” and warning her to “escape as for your life from this vortex of fanaticism.”

This is clearly an anti-Mormon letter and for this reason the pamphlet was considered an anti-Mormon publication. Accordingly, it was not included in Peter Crawley’s descriptive bibliography or in the original print version of Flake and Draper’s Mormon bibliography. Copies of the pamphlet in other library collections are cataloged with De Witt as its author.

But the pamphlet was not assembled by Rev. De Witt. His letter is presented first so that the girl he attacked could rhetorically demolish it.

Sarah Stageman had been born in England in 1826. When she was 14 years old, she had immigrated to Maryland with her parents and four younger siblings. While in her early twenties, she met and listened to Latter-day Saint missionaries. In her excitement, she consulted with Anna De Witt, who obviously informed her pastor husband. Rev. De Witt poured his scorn into a critical letter that he asked Sarah to share with her family and friends. He followed his own advice by repeating his written message in whispers to his flock. Sarah followed his counsel by publishing his folly.

Sarah begins by pointing out that De Witt had not cited any scripture in his 3 ½ page letter. Accordingly, her 8 ½ page response is a virtual tour de force of the Bible that cites more than 40 passages to testify of the truth of the Restoration, the last days, visions and revelations, Joseph Smith as a true prophet, the apostasy, the gathering of Israel, gospel dispensations, the restoration of priesthood authority, and the workings of God in His own way.

When asked by De Witt how she “made the discovery that Mr. and Mrs. De Witt, and the members of Rock Church and of other Churches, have no religion,” Sarah admits that it came with no help from him. “You inquire of me, if I have clearer views of my need of the ‘Holy Spirit.’ I answer, yes! But, was I confirmed by you, in the laying on of hands, to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit;–as was done by the Apostles”?

Sarah likewise had a ready answer for De Witt’s criticism of Joseph Smith. “You say if Joseph Smith was inspired, why did he locate that temple where it would be begun, but never finished: If he had, you would believe. But the Lord works in his own way. There is a city in Ezekiel we do not read of being built.” She pegged De Witt as like unto the unbelievers of an earlier scriptural age: “I say thus it is now, as it was in the days of Christ. In Mark, Chap. 15, ‘They said, let the king of Israel descend from the Cross, that we may see and believe.’”

No, this is definitely not an anti-Mormon pamphlet. Rather, it is a record of the significance of conversion in the life of a young woman newly converted to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. Its recovery from misunderstanding exemplifies of one of the ways we might re-engage historical sources to see the significance of conversion in the study of Mormon history.

Citation:

Correspondence between Rev. Abraham De Witt, pastor of Rock Church, Cecil Co., Md. and Miss Sarah Stageman, one of his flock, regarding the principles and faith of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Philadelphia: Bicking & Guilbert, Printers, 1849).

- Read the full pamphlet here (digitized in the Church History Catalog).

- See information about the pamphlet in the Church History Catalog.

- Browse other items in the Church History Library by and about Sarah Stageman.

[Note: This discovery and its story were shared as part of a talk I gave at the Church History Symposium.]

Tags

Access Policy Analogies Angel Moroni Archives & libraries Awards Black history Careers in History Church History Library Church History Speaking Come Follow Me Commemoration Conspiracy Theories Contingent Citizens Databases Elvis Presley Forgery Everybody's History Family History & Genealogy First Vision Foundations of Faith Genealogy Speaking History Skills History teaching & learning Hoaxes and History 2019 How History Works In the Church News Kirtland Temple Lincoln Making Sense of Your Patriarchal Blessing Missionaries Mormon studies Mormon Women's History Mother's Day Patriarchal Blessings Pioneers Politics Primary sources Questions and Answers RealvsRumor Saints Saints (narrative history) Sensible History Stories Texas social studies UTEP Centennial WitnessesDisclaimer

The views expressed here are the opinions of Keith A. Erekson and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Church History Department or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.