The cover of Contingent Citizens features a photograph of the Salt Lake Temple draped in an enormous American flag. We thought this juxtaposition—church and state, piety and patriotism, sacred and secular—captured the complex and contradictory ways that Latter-day Saints have been perceived in American politics. In the book we tease out the tensions clustered around authority and mobilization, power and sovereignty, and unity and nationalism. But the image prompts other interesting questions about the flag itself and how it ended up on the side of the Church’s most well-known Temple.

Why such a large flag?

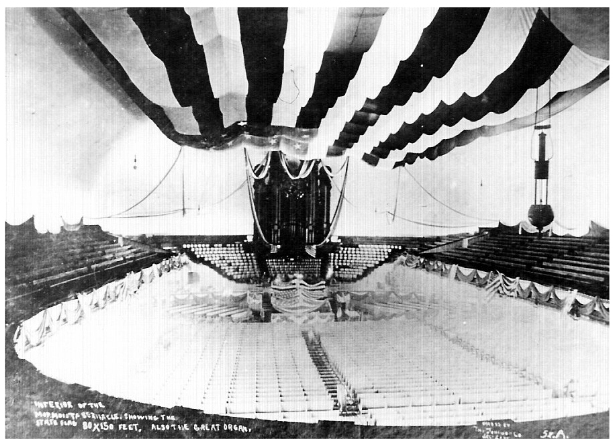

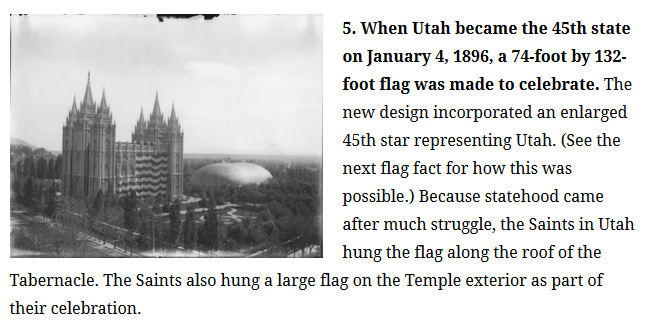

The flag was created to celebrate Utah’s admission as a state in 1896. With dimensions of 132 feet by 74 feet, it was designed to be “the largest flag in history” and it held that title until 1923. U.S. President Grover Cleveland signed the proclamation admitting Utah on January 4 and on January 6 an inauguration ceremony was held in the Tabernacle on Temple Square. The flag covered most of the ceiling and at the specified moment in the program a switch was flipped to illuminate Utah’s new 45th star on the flag.

Why was it hung that way?

The flag remained in the Tabernacle for several months, but as plans developed to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the pioneers in 1897, the large flag needed to find a new home. Over the next six years, until around 1903, it hung on the south side of the temple for appropriate holidays.

No records survive to document why the flag was hung in this way, but contextual information provides some clues. The flag would have fit on the north or south sides of the Temple, and they chose the south. The flag had two sides (the side with the blue union on the left hung in the Tabernacle), so they chose the side with the union on the right. Placement on the south side of the Temple made the flag visible to the more numerous city streets to the south. The Temple’s tallest towers on the east (with the angel Moroni at center) serve symbolically as the flagpole, with the colors thus flying in the breeze as it moves forward to the east. It was not until 1942 that the U.S. Congress adopted the United States Flag Code, with its prescriptions for flag hanging. Thus, there were no official instructions in 1897, but a circular from the U.S. War Department’s adjutant general issued in 1917 recommended that flags hung flat on walls should be oriented with the union to the north or east.

It is okay that the past was different?

Of course. As we seek to make sense of the pieces of the past and the stories told about it, we discover people, places, experiences, and traditions different from our own. The hanging of the flag “backwards” was not intended as a sign of disrespect or defiance. It did not preemptively break a flag code that would be passed half a century later. It was an appropriate part of its own time and place.

One artist who painted the scene as a romanticized pastoral landscape, felt no qualms about removing of all of the buildings and other signs of urban life, but nevertheless felt the need to explain: “This image accurately depicts how the flag was hung. There was no flag-displaying protocol at that time.”

Perhaps suspecting that its modern readers would be embarrassed, a magazine catering to the lives of Latter-day Saints inverted the image, a move made obvious by the presence of foothills in downtown Salt Lake City on the left edge of the photo.

Sources

The image on the cover of Contingent Citizens comes from the George W. Reed Photograph Collection the at the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library’s Special Collections.

For more on the history of this and other large flags, see John M. Hartvigsen, “Utah’s Mammoth Statehood Flag,” Raven: A Journal of Vexillology 19 (2012): 27–56. (Vexillology is the study of flags, their designs, histories, and uses.)